We often write about famous people’s wills — usually when they have died recently. So, for instance, we recently wrote about Anne Heche’s will. More accurately, we wrote about what might be her will. Sometimes we discuss the absence of a will, or other poor planning choices. Consider the continuing mess generated by Prince’s failure to plan his estate.

Why are these stories interesting — to us, or to you? Because we are often surprised about people with money and power and their failure to plan appropriately. No doubt there is a heavy dollop of schadenfreude involved. But there are often also lessons we can learn from the experiences of the rich, connected and recently deceased. Herewith a few of our favorite stories, and the lessons we can learn from them.

Anna Nicole Smith

She was born as Vickie Lynn Hogan in 1967. She was 39 when she died of a drug overdose in Florida. In those few decades, she had become famous for her looks, for her (limited) acting ability, for her marriage (to billionaire J. Howard Marshall) and for her tragic life story.

How does Anna Nicole Smith raise questions about famous people’s wills? She did it by being so very, very certain of her wishes when she signed her will.

In 2001, when Smith signed her final will, she had one child — her son Daniel, on whom she doted. J. Howard Marshall had been dead for several years, and she was deeply embroiled in probate litigation with his son. She could not imagine ever having anyone so close to her heart as Daniel.

Smith’s will included this unusual provision: “…I have intentionally omitted to provide for my spouse and other heirs, including future spouses and children and other descendants now living and those hereafter born or adopted, as well as existing and future stepchildren and foster children.” Presumably, it made sense to her at the time.

Within a few years, though, her world had changed. She had a new child, daughter Dannielynn, who was just a few months old when Ms. Smith died. And her beloved son Daniel died of a drug overdose very shortly after Danielynn’s birth.

So Smith’s will seemed to leave her estate going to no one. Extensive and difficult legal proceedings seemed inevitable. Ultimately, the courts directed her entire estate to her daughter — and left three men vying in court to be identified as the father. If Ms. Smith had simply acknowledged the possibility of having more children, her will might have been more straightforward.

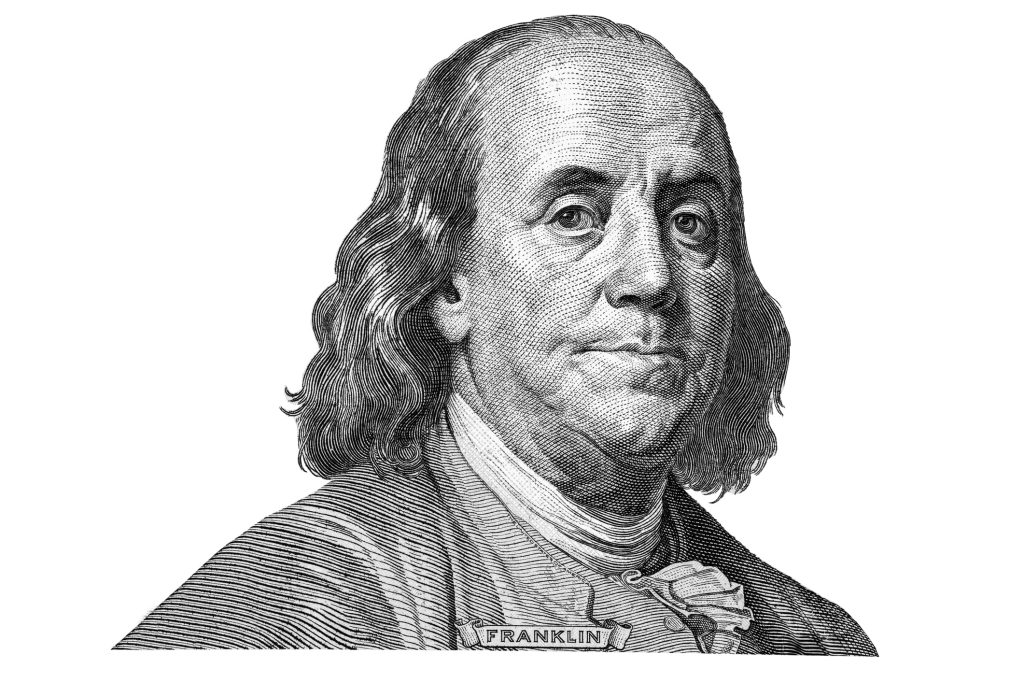

Benjamin Franklin

Our most colorful founding father (and the competition was fierce) left an appropriately colorful will. It is often cited as the most famous of famous people’s wills.

After largely disinheriting his royalist son (with the mildly snarky explanation that he was leaving son William “no more of an estate he endeavoured to deprive me of”), he included provisions giving most of his estate to his son-in-law Richard Bache. But it was a codicil that Franklin added in 1789 that is the best example of unusual provisions in famous people’s wills.

Franklin left one thousand pounds sterling each to the cities of Philadelphia and Boston. His bequests directed both cities encourage young entrepreneurs and artisans to get started in business — the way he had started as a printer in his own youth. The two funds were slated to run for 200 years each, and be distributed to public works in the respective cities at the end of their runs.

As it turned out, neither city followed Franklin’s direction. But both managed to make their funds grow over the next two centuries. Franklin had bet on the new American state’s bright hopes — and his bequests might be said to have shown the value of investment in that future country. But they didn’t accomplish what he intended.

Leona Helmsley

Another illustration of the genre of famous people’s wills: Leona Helmsley, the “Queen of Mean.” When the New York hotelier died in 2007 (at age 87), she was remembered for her tyrannical behavior, her assertion that “only the little people” paid taxes, and her devotion to her companion, a Maltese dog named “Trouble.” Her will left $12 million of her $5 billion estate in a trust for Trouble.

Under the law of many states, trusts left for animals can be reduced by the probate court if they are judged to be excessive. The New York courts reduced Trouble’s inheritance to $2 million, and he lived in luxury for three years. He died at the ripe old age of 12 (84 in dog years, right?).

Gene Roddenberry

When the Star Trek creator died in 1991, he left an estate estimated at about $500 million. Most of that went to his widow, with $500,000 bequests to each of his children (from a prior marriage).

In this case, famous people’s wills sometimes look a lot like yours. As many people do today, Roddenberry left a “no contest” (sometimes called “in terrorem“) provision in his will. If anyone contested the will’s terms, they would be disinherited. That’s exactly what happened to his daughter Dawn.

Dawn Roddenberry engaged in two years of legal proceedings trying to establish evidence of undue influence on the part of his widow. At the end of that process, the New York probate judge ruled that she would be treated as having predeceased her father. In other words, she would get nothing.

But the more famous element of Roddenberry’s will was a provision that asked that his ashes be scattered in space. A year after his death a portion of his ashes traveled into space but returned. Five years later, Roddenberry’s ashes — along with those of Timothy Leary and 22 other people — were in fact broadcast into space. So, you see, famous people’s wills aren’t like yours — or ours.