OCTOBER 31, 2016 VOLUME 23 NUMBER 41

In our legal practice, we frequently deal with individuals with limited capacity. Sometimes we speak of them being “incapacitated” or “incompetent.” Sometimes they are “disabled,” or qualify as “vulnerable adults,” or are subject to “undue influence.” But each of those terms means something specific, and some variations even do double duty (with two related but distinct meanings). A recent California case pointed out the confusion engendered when litigants rely on similar but different terms.

Aaron, a widower in his late 90s, lived alone after the death of his wife Barbara. He had no children of his own, though he and his wife had raised Barbara’s daughter Connie together after their marriage — when Connie was four. Aaron’s other nearest relatives were two nieces, Cynthia and Diane. He didn’t have much contact with Cynthia and Diane, though that might have been because his late wife had discouraged contact over the years they were together.

Connie was actively involved in overseeing Aaron’s care. She arranged for his doctor’s visits, went to his home at least twice a week to check on him, helped pay his bills and generally watched out for him. She was concerned about his ability to stay at home, and on several occasions she found herself summoning the local police to make welfare checks on her stepfather.

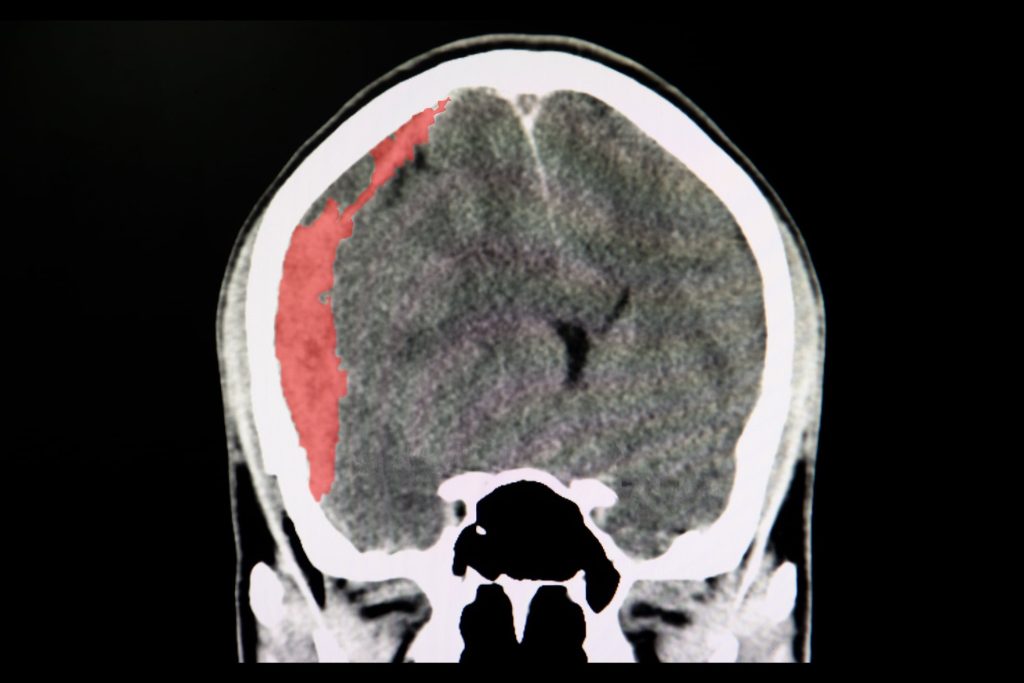

After Aaron fell in his home, refused treatment, and suffered a frightening seizure, he was diagnosed as having a subdural hematoma (from his fall). He spent some time in a hospital, but was anxious to return home. His physician noted that he had a poor score on the mental status exam administered in the hospital, and diagnosed him as having dementia. He was discharged to a nursing facility, with Connie’s help.

Aaron hated the nursing home, and the assisted living facility Connie helped move him to after that. He insisted that he could return to his own home. About this time, his nieces began to visit him, and they tried to assist. They disagreed with his placement, and niece Cynthia prepared a power of attorney for Aaron to sign, giving her authority over his personal and financial decisions. After he signed the document, he asked his attorney to write to Connie, asking her to return his keys and personal possessions so that he could return home.

Connie filed a petition for her own appointment as conservator of Aaron’s person and estate (California, confusingly, refers to guardianship of the person as conservatorship). While that proceeding was pending, Aaron went to his attorney’s office and changed his estate plan — instead of leaving everything to Connie, he would split his estate into three equal shares, with one each for Cynthia, Diane and Connie’s daughter.

The probate judge heard evidence in connection with Connie’s conservatorship petition, but denied her request. The judge found that Aaron was clearly subject to undue influence, and might lack testamentary capacity — but he didn’t need a conservator (of his person or his estate).

How could that be? Connie appealed, but the California Court of Appeals ruled that the probate judge was correct. At the time of the hearing on the conservatorship petition, according to the appellate court, Aaron was alert, oriented and able to describe his wishes. The fact that he might have been incapacitated when he signed the powers of attorney, or that he might have been subject to undue influence when he changed his estate plan, was not dispositive of the question of his capacity at the time of the conservatorship hearing. Furthermore, the mere fact of incapacity would not be enough; by the time of the trial Aaron had a live-in caregiver who could help him manage his daily needs, and that could support the probate judge’s determination that no conservator (especially of the person) would be necessary.

Aaron and his attorney also argued that Connie didn’t actually have any standing to file a court action in the first place. After all, she was his stepdaughter, and not even a blood relative. The Court of Appeals rejected that notion; any person with a legitimate interest in the welfare of a person of diminished capacity has the authority to initiate a conservatorship proceeding. Conservatorship of Mills, October 20, 2016.

So what do the various terms mean, and how are they different? “Capacity” (and “competence”) usually refers to the ability to make and communicate informed decisions. “Testamentary” capacity is a subcategory, and requires that the signer of a will must have an understanding of his or her relatives and assets, and the ability to form an intention to leave property in a specified manner. “Vulnerable adult” is a related term, but is used in most state laws to refer to a person whose capacity is diminished, and whose susceptibility to manipulation or abuse is therefore heightened. “Undue influence” can arise because of limited capacity, but refers to the actions of third persons which overpower the individual’s own decision-making ability. “Disability” is, perhaps, the least useful of the terms — attaching the term does not say much about an individual’s ability to make their own decisions, since disabilities can be slight or profound, physical or mental (or, of course, both), and subject to adaptive improvement in any case.

In Aaron’s case, it might well be that his amended estate plan will be found to have been invalid as a result of undue influence, and his new powers of attorney might be set aside on the same basis. He might even be found to have been a vulnerable adult and any transactions benefiting his nieces might be subject to challenge. But he apparently had the level of capacity necessary to make his own personal and financial decisions at the time of the hearing on the conservatorship petition.

As an aside, there’s another issue in Aaron’s court decision: the inappropriate reliance on scores obtained on short mental status examinations. Typically, medical practitioners ask a short series of questions (“What is the year?”, “Please repeat this phrase: ‘no ifs, ands or buts'” and the like) as a way of determining whether further inquiry should be made into dementia and capacity questions. Aaron variously scored 14, 18, 24 and 20 on 30-point tests administered by several interviewers, and both the probate court and the Court of Appeals seem to have thought that the results demonstrated his fluctuating capacity (and general improvement). Those scores are only suggestive of incapacity, and should be an indicator that further testing might be appropriate. There is no bright-line score for determining incapacity on the basis of those short examinations.