A recent Arizona appellate case raised a novel question. Can a trust protector’s amendment be challenged by the trust’s beneficiaries?

Austin Bates and his family

To understand the appellate decision — and the effect it might have on others — it helps to know the family involved. From the reported decision and a quick check online, Austin Bates’ story emerges:

Mr. Bates was 81 when he died in 2018. He had struggled with Parkinson’s disease for several years. He left behind an ex-wife and three daughters. Shortly after his 2016 divorce from his wife of 57 years, he remarried. His new wife, Lindi Davis Bates, had been his caretaker for some time before the marriage.

Just before his divorce was final, Mr. Bates retained Phoenix attorney Paul Deloughery (who now runs a company called “Sudden Wealth Protection“) to prepare a trust for him. Mr. Deloughery drafted a document that created an irrevocable trust. It named a private professional fiduciary company as trustee. It also included provisions for a “trust protector” — someone who could amend the trust, change beneficiaries and make other kinds of changes. Who would be the trust protector? Mr. Deloughery.

The trust was for Mr. Bates’ own benefit for the rest of his life. As first written, after his death it divided 45% to his ex-wife, 45% among his three daughters, and 10% to his then-girlfriend Lindi Davis.

Why an irrevocable trust?

Most trusts established for the benefit of a living person, using their own money, are created to be fully revocable and amendable. Why did Mr. Bates make his trust irrevocable?

At the time he first met with Mr. Deloughery, Mr. Bates expressed his concern that the “women in his life” might exert “too much pressure on him to change his estate plan.” Making the trust irrevocable would help protect against that possibility. It could also protect him from exploitation and any undue influence.

At the same time, the inclusion of a trust protector would mean that someone could make necessary changes over the years following establishment of the irrevocable trust. That would give Mr. Bates the comfort and peace of mind that he would not have to deal with disputes among his ex-wife, his daughters and his new wife. At the same time, it would provide flexibility to deal with changes.

The trust protector’s amendments

Within six months of the trust’s creation, the trust protector had signed two amendments. The first added a new provision: an “in terrorem” clause that would automatically disinherit anyone who challenged the trust or its terms. The second one changed the beneficiaries altogether.

The second amendment, signed by the trust protector in May, 2017, removed the 45/45/10 split among Mr. Bates’ ex-wife, daughters and new wife. Instead, it continued his entire trust estate for the rest of his new wife’s life, allowing the trustee to distribute any share he or she deemed appropriate to the new wife. Whatever was left on the death of the new Lindi Bates would go to Mr. Bates’ three daughters and Lindi Bates’ sons from a prior marriage.

Can a trust protector’s amendment delete beneficiaries, change shares and add entirely new beneficiaries? Yes, if the document permits it. And the document drafted by Mr. Deloughery — and relied on by Mr. Deloughery when he amended the trust — did just that.

In the later litigation, it became apparent that the changes were initiated by the new Mrs. Bates’ insistence that her husband wanted the trust protector to act. But wasn’t the trust protector supposed to be a barrier against just such actions? Yes, but Mr. Deloughery was apparently persuaded that it was consistent with Mr. Bates’ wishes and in keeping with the general purposes of the trust.

Lindi Bates takes control

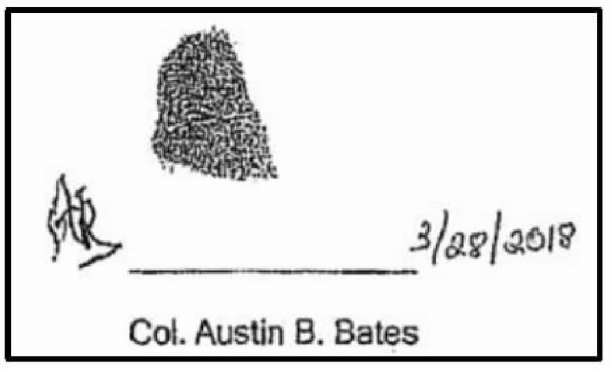

Meanwhile, the new Mrs. Bates began managing the trust’s assets — rather than turning them over to the named trustee. She collected rents from tenants of properties owned by the trust, she raised their rents, and she arranged for refinancing. She also moved to replace the trustee with a friend. When the named trustee resigned, she had her friend appointed to the position by an authorization “signed” by Mr. Bates — his thumbprint signature appears above.

Mrs. Bates also demanded that Mr. Deloughery, as trust protector, amend the trust one more time. This time she insisted that the trust’s assets should be distributed outright to her on her husband’s death, rather than continuing in trust. Rather than accede to her demands, Mr. Deloughery resigned as trust protector.

Mr. Bates died in 2018 in Ketchum, Idaho (Mr. Bates was a retired airline pilot — in one of his two obituaries it was said that he “flew West“, a common pilot expression). Lindi Bates was soon under fire from his first family.

The lawsuit

Mr. Bates’ three daughters and ex-wife sued to invalidate the second amendment because, they said, it was the product of undue influence by Lindi Bates. They sued the new Mrs. Bates herself, rather than the trust protector. Their assertion: thae amendment was occasioned by Lindi Bates’ insistence that her husband seek the change, and her undue influence on him in requesting that the trust protector act.

The Maricopa County (Phoenix) probate court dismissed the complaint, finding that any undue influence on Mr. Bates was irrelevant to the trust protector’s actions. The probate judge also ruled that the challenge had triggered the trust’s “in terrorem” provision. Mr. Bates’ daughters and ex-wife would therefore receive nothing from the trust.

Mr. Bates’ first family appealed. Last week, the Arizona Court of Appeals found in their favor, reversing the probate court and remanding for further proceedings. One of the three judges on the panel dissented, and would have upheld the probate court ruling.

The Court of Appeals ruling

According to the two appellate judges in the majority, the claim of undue influence could be sustained in the particular facts of the case. If the family proves their claims that Lindi Bates was active in the procurement of the amendment, and unduly influenced her husband in making his request to the trust protector, the fact that he did not make the change himself would not shield her from an undue influence claim. The probate court should consider the first family’s assertion that Mr. Deloughery did not exercise independent judgment at all, and instead followed or acted upon Mr. Bates’ instructions — which were alleged to be the product of his wife’s undue influence.

The dissenting judge argued that the family should have been required to show that Lindi Bates unduly influenced Paul Deloughery, the trust protector — which they had not even alleged. Both the majority and the dissenting judge agreed that the question was unusual, and that no precedent seemed to be available in Arizona or any other state. Bates v. Bates, May 11, 2021.

Is there a deeper meaning, or message?

At Fleming & Curti, PLC, we frequently suggest the use of a trust protector. It can be a good way to allow for flexibility to adjust for unforeseen changes in circumstances. We have seen enough older trusts with now-unworkable provisions that we prize that flexibility.

Any trust naming one, though, should give the trust protector specific directions and some limitations. Should a trust protector always have the power to change beneficiaries? No. Should the trust protector have authority to name new trustees when needed? Probably. But each case is different, of course.

What about a lawyer naming himself as trust protector? We do it from time to time. But we try to be clear about what authority we take on, and what we will not do. And when we do act under the authority given by the trust protector provision, we try to prevent exactly the kind of problems that developed in the Bates case.

We often see aging clients who worry about the prospect of further deterioration and the blandishments of overly-aggressive family. The idea of an irrevocable trust to help protect against that can be attractive. But the key is not so much to protect family harmony as it is to protect our client’s peace of mind that they can be free from the pressures and insistence of close family members.