You’ve probably seen the terms before. “Right of representation” and “per stirpes” appear frequently in wills and trusts. You probably even have a rough notion of what the terms mean. Perhaps, though, you don’t know that they have an interesting history. You might also be surprised by what the terms actually mean — at least in Arizona.

Relationship to “intestate succession”

The rules governing what “right of representation” and “per stirpes” mean are actually echoes of the rules governing distribution of property for people who have not signed a will. “Intestate succession” is the legal term for the process of figuring out who gets what when no estate plan has been written.

In Arizona, if a single person dies leaving, say, four surviving children (and no spouse, and no deceased children), the intestate succession rules are simple and clear. The decedent’s estate will be divided equally among the four children. That’s what intestate succession is all about.

What happens, though, if one or more of the decedent’s children have died before she dies? Do their spouses, or their children, receive their share?

The short answer is that a deceased child’s share normally flows to that child’s offspring (but not to the deceased child’s spouse). But the precise way that works can be a surprise for many.

Let’s try a chart to explain how this works

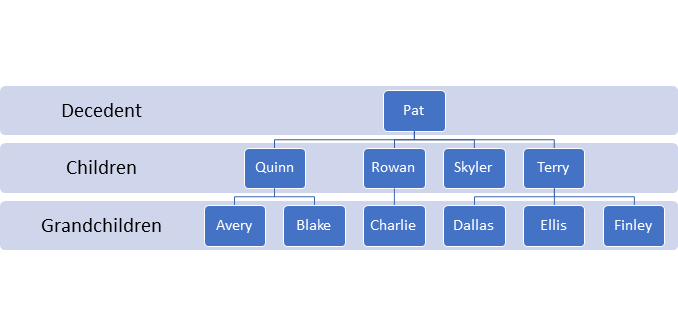

Consider Pat, a single person with four children. Pat died without ever signing a will or naming beneficiaries on individual accounts. Here’s a graphical representation of Pat’s family:

Assuming all of Pat’s children are living, they will share Pat’s estate equally. But what if, say, Rowan and Terry had died before Pat?

Confusingly, there are at least three ways to calculate the shares each of Pat’s offspring would receive. In the facts given, two of them give the same result — but one changes what many people might expect. In fact, the third option changes what most lawyers would describe.

“English” (or traditional) per stirpes

In our scenario, both Rowan and Terry died before Pat. Rowan had one child, and Terry had three.

The traditional method of calculating shares would be to divide Pat’s estate into four equal parts. Why four? Because each of Pat’s children gets a share, and each deceased child who left children has his or her share divided among their branch of the family. In fact, “branch” is a key word here — “per stirpes“, the term describing how Pat’s estate would be divided, is just Latin for “by the branch”.

One share of Pat’s estate will go to Quinn, and a second one to Skyler. The shares that would have gone to Rowan and Terry will be divided among their children. Rowan’s one-fourth will go to Charlie, and Terry’s one-fourth will be divided into three equal shares. Dallas, Ellis and Finley will each receive one-twelfth of Pat’s estate.

That’s what most people probably expect, and it might be referred to as “representation” (Charlie, Dallas, Ellis and Finley stand in for their respective parents, or represent that share of the estate) or “per stirpes”. In this context, the terms are largely interchangeable. About a third of American states still adhere to this traditional per stirpes notion.

“Modern” per stirpes

A newer approach, adopted in a number of American states, treats the right of representation slightly differently. It would not make any difference for Pat’s estate, since at least one of the children survived.

Under the traditional approach to the right of representation, if all four of Pat’s children had died, each of the grandchildren would receive their portion of their deceased parent’s share. Since Skyler has now died without issue, that “branch” is simply distinguished. In other words, Avery and Blake would split one-third of Pat’s estate, Charlie would receive a full third, and the final third would be divided equally among Dallas, Ellis and Finley.

But under the “modern” notion of intestate succession, a different result would occur. Because no member of the first generation survived, the modern approach would look to the next level — and Pat’s estate would be divided into six shares. Avery, Blake, Charlie, Dallas, Ellis and Finley would all get an equal inheritance. There is no longer any penalty for a grandchild having come from a larger family branch.

This “modern” per stirpes approach to the right of representation has been adopted by about half of the American states. That variation doesn’t show up very often, though — it requires Pat to have at least a couple of children, all of whom have died leaving children of their own.

Arizona’s approach is different

There is a third approach, first developed about twenty years ago. Arizona (somewhat surprisingly) is in the vanguard in adopting the new approach. Our statute modifying the meaning of “right of representation” has been in place since 1994.

The Arizona notion of the right of representation is usually described as “per capita at each generation”. What does that mean?

Under Arizona’s intestate succession statute, Pat’s estate would be divided into four shares, just as with traditional per stirpes. One share would go to Quinn and another to Skyler, just as with traditional per stirpes.

The remaining two shares, though, would be handled differently. They would be re-accumulated, and then divided equally among the next generation — but only those members of the next generation whose parents had predeceased Pat. In other words, one-half of Pat’s estate would be divided equally among Charley, Dallas, Ellis and Finley. Each would receive one-eighth of Pat’s estate.

What if I want to change Arizona’s right of representation?

You can. It’s a simple matter, actually — you just have to specify a different methodology in your will, trust or beneficiary designation.

Under Arizona law, you can opt out of the “per capita at each generation” approach by using the term “per stirpes”. If you do, then you have elected the English, or traditional, per stirpes approach.

Use the phrase “by representation” or “by right of representation” in an Arizona will and you have opted to apply Arizona’s “per capita at each generation” approach. If you say nothing, or if you simply say “to my children,” you’ve probably adopted the Arizona default rule of “per capita at each generation” and you might have encouraged litigation to figure out the correct answer. But that’s another story for another day.

What happens if Pat is married, or if some of Pat’s children are adopted, or … well, you get the point. Changes in the facts will, of course, change the result. A lot. We’re just going through this fact pattern as it is, in order to illustrate the issues.

Do you find all of this confusing? That’s why you might talk with a Tucson elder law attorney before signing your will, trust or beneficiary designation. We’ll help you figure out how the rules apply in your family situation.