Most people understand the concept of joint tenancy ownership. But the operation of joint tenancy in specific facts may be counterintuitive. Last week we read an Illinois case that pointed out that joint tenancy is not just joint ownership of property.

The life of a joint tenant

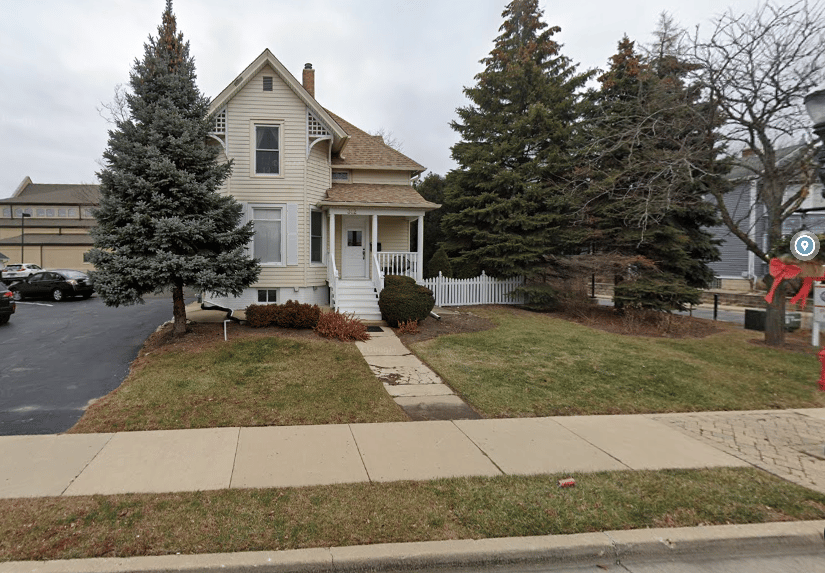

Victor Barcroft lived in Lake County, Illinois, where he owned and operated funeral homes over a number of years. During those years he also acquired various pieces of real estate in the county. Included in those properties: a home and lot in Barrington, Illinois.

In July, 2000, Victor transferred the property in Barrington into joint tenancy between himself and his daughter Susan. Susan, perhaps not incidentally, owned and operated a business next door to the property. That set up the later legal challenge about the operation of the joint tenancy.

To be clear, joint tenancy property ownership is a popular way to plan (or fail to plan, in some cases) one’s estate. The full name of the title arrangement: “joint tenancy with right of survivorship.” That means that the usual operation of joint tenancy is to permit the surviving joint tenant (or joint tenants — there can be multiple co-owners) to receive the property automatically on death of one joint tenant.

In 2016, a Florida woman filed a breach-of-contract claim against Victor in that state. She obtained a judgment against him, and assigned her judgment to another woman to try to collect against Victor.

Her assignee, Barbara Bergstrom, went looking for Illinois property to collect against. She found the property in Barrington, and recorded her Florida judgment in Lake County. Then, beginning in 2019, she started a lawsuit to foreclose on the property.

The death of a joint tenant

Several other parties were added to the lawsuit over the next year, including a friend who was alleged to have loaned money on the property, and the two tenants. But Victor Barcroft died on November 2, 2020, before the lawsuit was resolved.

Susan Barcroft was already a party to the lawsuit seeking foreclosure. But she was not a defendant in the underlying Florida case. She moved to dismiss the foreclosure lawsuit.

According to Susan Barcroft’s theory, the operation of the joint tenancy title meant that she now owned 100% of the property. There was no longer any share belonging to her father, or to her father’s estate. The plaintiff had nothing to recover against.

But wait, argued the plaintiff. When we filed our lawsuit, and recorded a lien, we locked in our claim. Victor couldn’t defeat our claim by simply dying.

Yes, ruled the trial judge, he could. That’s the basic operation of joint tenancy at work. The surviving joint tenant simply acquires the deceased joint tenant’s interest — automatically.

The Court of Appeals

The plaintiff appealed her loss to the Appellate Court of Illinois. Last week the court of appeals agreed with the trial judge, and upheld dismissal of the foreclosure action.

According to the appeal decision, joint tenancy is not just a co-ownership arrangement. Susan Barcroft, the surviving joint tenant, acquired her ultimate interest at the time of creation of the joint tenancy, back in 2000. When her father died, her interest automatically increased to full ownership. His estate had no interest in the property. That, according the appellate court, is the basic operation of joint tenancy. Westberg v. Barcroft, August 31, 2022.

Would the same rule apply in Arizona?

Likely, but it is not completely clear. The operation of joint tenancy has been the subject of a surprisingly small number of Arizona laws or court cases.

One recent Arizona appellate decision (but an unreported one, it should be noted) seems to give support to the same analysis, at least. But the issue in that case was more about whether the decedent had actually intended to create the joint tenancy rather than the operation of the joint tenancy after his death.

Another, older Arizona case addressed whether a joint tenant’s interest in property could be reached by a creditor of just one of the joint tenants. But it didn’t involve the death of a joint tenant.

To confuse things further, there is at least some suggestion in Arizona’s probate law that a creditor could seek to bring joint tenancy property other than real estate back into the deceased joint tenant’s estate to satisfy claims. But even if applicable, that statute would (at a minimum) require a probate proceeding and an adversary action seeking to reclaim the property. In practice, that makes further action unattractive, even if legal.

It is abundantly clear, however, that a creditor protection plan that requires the creditor to die is an unattractive alternative. But when it happens — at least in Illinois — it can be an effective technique.